Have you ever stopped to ask yourself: What is the history of the land I’m standing on? Through whose hands has it passed ownership? How can we acknowledge these histories?

Throughout all HMI programs, a key part of our school’s mission is to engage students with the natural world.

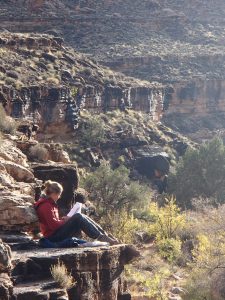

During the HMI Semester, each student takes the course “Practices and Principles; Ethics of the Natural World.” This class is designed to “challenge [students] to think critically about the way in which [they]…interact with, use and think of the natural world.” HMI Semester students spend roughly one-third of their semester sleeping under the stars, and exploring what it means to be a thoughtful citizen and steward of the places we travel through.

“Practices and Principles; Ethics of the Natural World.” This class is designed to “challenge [students] to think critically about the way in which [they]…interact with, use and think of the natural world.” HMI Semester students spend roughly one-third of their semester sleeping under the stars, and exploring what it means to be a thoughtful citizen and steward of the places we travel through.

During our Gap Semesters, students complete a robust Environment Studies curriculum. We ask them to consider: “Are humans part of, or separate, from nature?” Gap students spend close to 60 days immersed in a backcountry environment.

Fundamental to any HMI student experience is this bold union of rigorous intellectual inquiry and experiential learning.

We hope that out of our students’ inquiry into the land we live, learn and play on, and through their experiences with it, that they develop what we call a “ sense of place.”

To have a “sense of place” is to have a connection, relationship, or attachment to a place that results from experiences and memories associated with a place. Through a rooted understanding of “sense of place,” people form values associated with land. Land holds many emotions for humans: it is nostalgic, it is peaceful, it is traumatic or it is sacred. Sometimes land is “useful” or deemed “useless.”

Our students, current and former, are connected by powerful associations with the land that we built our school on. These places feel uniquely “ours.” The sense of belonging these shared places foster are why when any alumni walk in the door at HMI for a visit we say “welcome home.”

The lands our community associates as home—the deep canyons of Bears Ears National Monument, the alpine tundra in San Isabel National Forest, or the sagebrush field behind Who’s Hall—were all once home to different peoples. We believe that it is necessary to ground our students’ sense of place by first honoring the people that came before us.

The Ute have hunted game and fished trout in the Sawatch Range and Arkansas Valley for centuries—and many Ute continue to do so today. President Obama declared the Bears Ears region of Utah a  National Monument after an inter-tribal coalition made up of Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, Dine, and Ute leaders created a management plan “to assure…the area will forever be managed with the greatest environmental sensitivity…where [they] can be among [their] ancestors…where [they] can connect with the land and be healed.” Before settlers wiped out the entire indigenous populations of Chilean Patagonia, the Mapuche people created elaborate rock art inside their cave dwellings. The lands we love have been loved for centuries before us, and are still loved by indigenous communities today.

National Monument after an inter-tribal coalition made up of Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, Dine, and Ute leaders created a management plan “to assure…the area will forever be managed with the greatest environmental sensitivity…where [they] can be among [their] ancestors…where [they] can connect with the land and be healed.” Before settlers wiped out the entire indigenous populations of Chilean Patagonia, the Mapuche people created elaborate rock art inside their cave dwellings. The lands we love have been loved for centuries before us, and are still loved by indigenous communities today.

As we encourage students to develop a deep “sense of place” while they are at HMI, we must also help them understand that caring for the land we love is an ongoing, nuanced, and complicated act. Without acknowledging that our programs take place on lands with intricate and biased histories—lands that have changed hands from indigenous peoples through the often brutal tactics of Western Expansion—we would do a great disservice to the indigenous communities who spent centuries as the stewards and protectors of the places we love, and still continue to steward and protect them today.

To properly engage in the natural world is not an easy task. True engagement requires students to use all of the habits of mind that we hope to instill in them during their HMI experience: accountability and collaboration, critical analysis, curiosity and inquiry, and effective communication. We encourage our students, and the wider HMI community, to use these habits of mind when exploring topics of land stewardship and acknowledgement.

To properly engage in the natural world is not an easy task. True engagement requires students to use all of the habits of mind that we hope to instill in them during their HMI experience: accountability and collaboration, critical analysis, curiosity and inquiry, and effective communication. We encourage our students, and the wider HMI community, to use these habits of mind when exploring topics of land stewardship and acknowledgement.

One of the ways that HMI works to acknowledge the traditional indigenous inhabitants of public land is by including land acknowledgements on our social media posts. These land acknowledgements specifically identify the traditional indigenous inhabitants of the land that our students travel through while participating in HMI courses. The US Department of Arts and Culture, a grassroots organization working to shape a culture of empathy, equity, and belonging, writes, “Acknowledgement is a simple, powerful way of showing respect and a step toward correcting the stories and practices that erase Indigenous people’s history and culture and toward inviting and honoring the truth.” To read more about the practice of land acknowledgement, check out Honor Native Lands: A Guide and Call to Acknowledgement.

We hope that the HMI community at large will join us in acknowledging the traditional indigenous inhabitants of land throughout the United States, and world. We are proud to support land acknowledgement and are excited at the process of continuing to educate our students, and community, about the rich history of the places we have all come to love.