One of the most frequent questions I get asked when people learn that I have spent time in Antarctica is: do you see any polar bears while you’re there? There are no bears, polar or otherwise; Antarctica is the realm of the penguins. Fun fact: the ancient Greek word for bear is arktos, written as arctic in modern times, meaning north. So, arctic = bear, while anti-arctic = without bear.

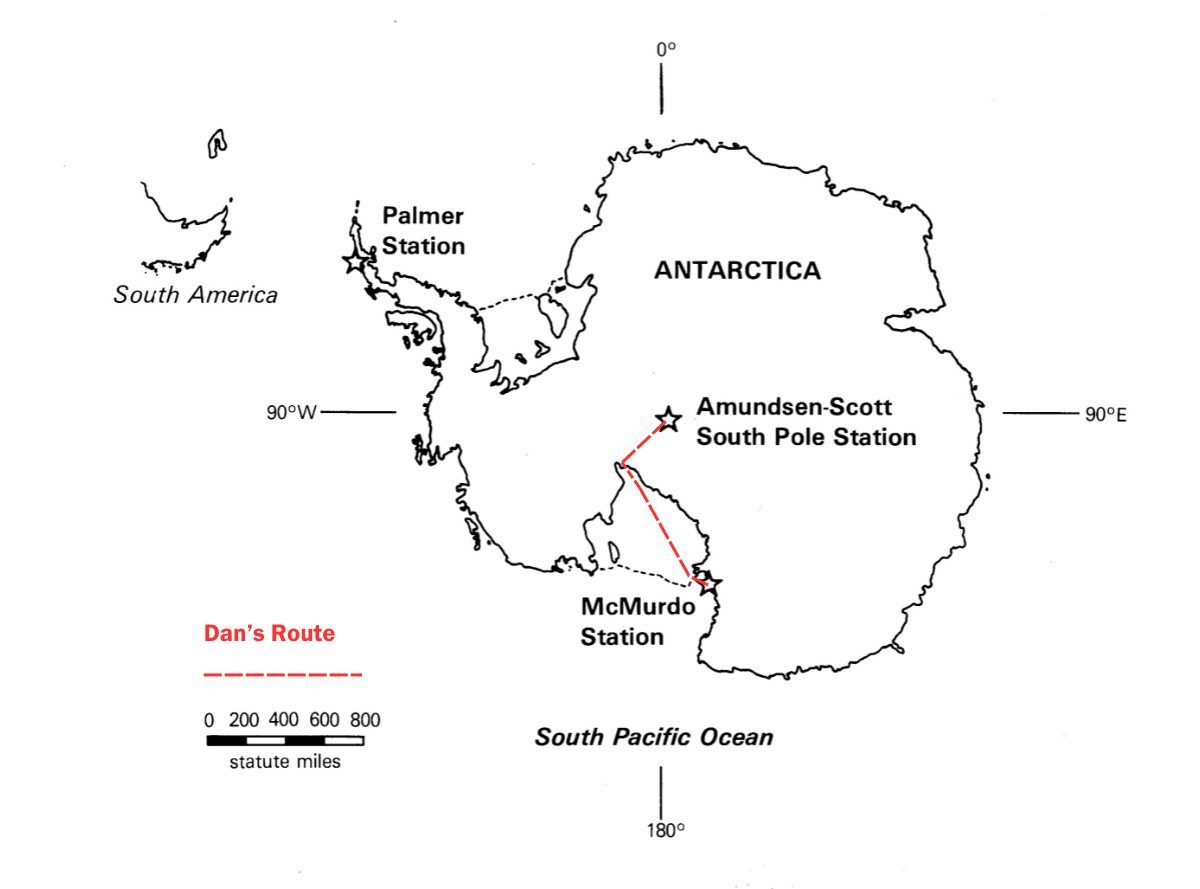

I have spent 12 austral summers, September through February, and one winter, February through September, in Antarctica or on “The Ice” as it is called within the United States Antarctic Program (USAP). Much of my time has been spent at McMurdo Station located on Ross Island, which is connected to the continent by the Ross Ice Shelf, a slow-moving, floating glacier between 40 and 2,300 feet thick that covers about 190,000 square miles, or roughly the area of France.

During my time on the Ice I have held several positions, all with the overall aim of supporting science in the highest, driest, windiest, and coldest place on earth. The past three summers I was part of the South Pole Traverse, or SPoT, which is tasked with hauling critical supplies and fuel to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, another important science hub.

While driving between McMurdo and the Pole I live with 11 other men and women, who for better or worse are the only people I will see for the 25-35 days it takes to complete the 1,038-mile journey each way. For much of the journey, beyond the 12 of us, the next closest humans are on the International Space Station.

Why does it take so long? For starters, we are hauling loads in excess of 200,000 lbs over soft snow and slick ice, and at times up a steep glacier through the Trans-Antarctic Mountains onto the polar plateau at an elevation of over 9,500 feet. While extremely powerful, our Caterpillar tractors have a maximum speed of 20 mph, but under these loads we are lucky to see 5 mph. Another factor is the weather, which at times produces winds and blowing snow that drop visibility to near zero, and brings temperatures that, on the plateau, can be well below -40 F with wind chills in the -80’s F. These temps make mechanical failures common and even minor repairs take much longer than they would if you weren’t laying in the snow and could feel your fingers.

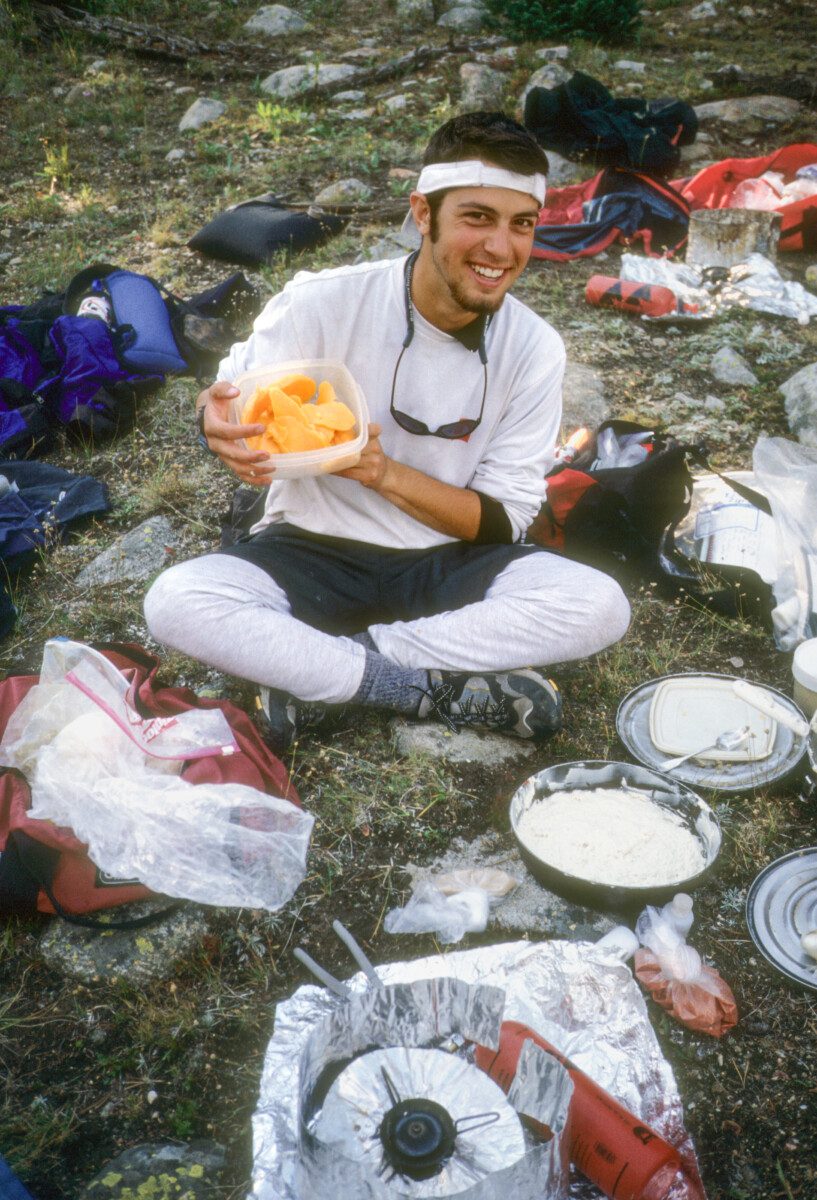

There are a lot of parallels between a South Pole journey and an HMI expedition. Besides the technical tasks of driving, tractor maintenance, taking turns cooking for the crew and doing community chores like cleaning and filling the snow melter for our drinking water, there are a lot of other, softer skills, that are needed to make this trip successful. Crew members come from diverse backgrounds and everyone has their own way of doing things. Some have never been part of a small team and have to learn how to be good community members. While not perfect, I have over my years working on the Ice and elsewhere in small groups, developed many of the skills, both hard and soft, that I was first introduced to on the RMS V trips in the Rocky Mountains and canyons of Utah.

I credit my semester at the High Mountain Institute with setting me on a path that directly lead to my unique outdoor career. After HMI, I graduated from Northampton High School in western Massachusetts, and got my first job in the outdoors on a trail crew in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. This in turn led me to Sterling College in northern Vermont, which then led me to Alaska, where I made a friend who had been to the Ice and who piqued my interest in Antarctica, where I have since spent more than a decade living and working, going so far south that every direction is north, and eventually meeting the person who would become my wife.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 HMI Newsletter.